by Danielle Jenkinson

Swansea Museum Documentation Officer

In celebration of Wales competing in the 2022 FIFA World Cup, we are going to look back at the only other time Wales has qualified, and talk about some of the Welsh players from Swansea who represented their country, or very nearly did.

In 1958, Wales were surprise participants in the World Cup held in Sweden. Having failed to qualify through the European section of the games, Wales were awarded a second chance to compete, this time as representatives of Asia-Africa. Due to political tensions surrounding Palestine and the Gaza Strip, Arab teams refused to play Israel for a place in the tournament. FIFA decided to organise a draw for the runners-up from other regions to advance through the Asia-Africa qualifiers. Wales were the team picked out of the hat; they won both their matches against Israel, and so headed for Sweden.

On April 18, 1958, the Welsh FA selectors met in Shrewsbury to decide on the World Cup squad. Seven players were clear choices: Jack Kelsey in goal, Mel Hopkins at left-back, the captain Dave Bowen at left-half, Ivor Allchurch at inside-left, Cliff Jones at outside-left, Terry Medwin, who could play at outside-right, inside-left and centre-forward if needed, and John Charles, the centre-forward who played for Juventus. Kesley, Allchurch, Jones, Medwin and Charles, were from Swansea.

Jack Kelsey was born in Llansamlet and played for Arsenal. He was not only one of the best goalkeepers in Britain, but also the world.

Ivor Allchurch, nicknamed the ‘Golden Boy’ in part due to his wavy blonde hair, was considered one of Wales’ few world-class players. Allchurch joined the Swans in 1947 after he was spotted playing youth football while a pupil at Plasmarl School. He made his league debut in 1949 and the following year he was playing for his country. Due to his decision to stay in Division 2 with the Swans he gained another nickname, ‘The Star Who Wasn’t Quite’, as it was felt by many that he was wasting his talents at The Vetch.

Cliff Jones was born into a famous football family, as his father and uncle both played for Wales. Brought up in the Sandfields area, ‘Cliffie’ made his league debut for Swansea Town in 1952 at the age of 17. However, Jones arrived in Sweden the most expensive winger in the Britain, as Tottenham had signed him that year for a record £35,000.

Terry Medwin was the son of a prison officer, and was born opposite The Vetch. When signed by his local club, they described him as “the lad from the prison next door”. Good-looking, he became popular with supporters and soon became the Swansea Town pin-up boy. When asked why he thought so many of the Welsh squad were from Swansea, Medwin replied:

“I think it had a lot to do with having a beach … Growing up in Swansea after the war there wasn’t much to do if you were young, so most of us played football all day long on the beaches. In a way, we had our own Copacabana.” (Risoli, 1998, p.27)

John Charles was the most famous and highly regarded player in the squad, and he remains one of the greatest footballers Wales has ever produced. After leaving school in 1946, he joined Swansea Town. However, before he could make his first senior appearance at The Vetch, he was sold to Leeds United in 1949. In 1957, believing he was the best centre-forward and centre-half in the world, Juventus signed him for a record breaking £67,000. During his first season in Italy, Charles had proved to be a sensation. Nicknamed ‘il Buono Gigante’ (the Gentle Giant), the six foot tall player finished the Serie A as the league’s top scorer, with 28 goals. This helped Juventus to win the championship for the first time in six years, and they re-signed him for £150,000. This placed him in the history books as the world’s most valuable footballer.

Although it was an obvious choice to place John Charles in the squad for Sweden, it was also a gamble. His participation in the World Cup was down to Juventus, and when the team was chosen, the club had not yet given its consent. This led to many negotiations with the club for the release of Charles to play for Wales, something Juventus was reluctant to do. It put their most valuable player at risk of injury in games that did not benefit them, and for a country that was not expected to do well in the tournament.

On that day in Shrewsbury, the selectors decided on 17 of the 18 players. The rest of the Sweden party would be Mel Charles, Stuart Williams, Derrick Sullivan, Trevor Edwards, Colin Webster, Vic Crowe, Roy Vernon, Ken Jones, Ken Leek and Colin Baker. Unfortunately, Ivor Allchurch’s brother, Len Allchurch, was not chosen. Although in the shadow of his older brother, the Swansea Town player was a good footballer in his own right. Mel actually played with John at Leeds in 1952, but he failed to feel comfortable in Yorkshire and returned to Swansea Town to play in their first-team.

The deliberation over the eighteenth man was a heart breaking one. It was between Manchester United winger Ken Morgans, a survivor of the Munich Air Disaster, and Cardiff City’s Ron Hewitt; the selectors eventually chose Hewitt. They had planned to watch Morgans in the FA Cup final, but when it was announced that the 18-year-old was not physically or mentally fit enough to play; he missed his opportunity to represent Wales.

Swansea-born Morgans had been the youngest of the ‘Busby Babes’, a group of young footballers who had all progressed together from Manchester United’s youth team into the first team under the management of Matt Busby. Many of the young players died in the Munich Air Disaster of 1958; Morgans was the last person to be found alive amongst the wreckage. Doctors recommended he should take a year off football, but because of the shortage of first-team players, he was back playing for United seven weeks later. In an interview he shared his experience of that time:

“I felt dreadful. I’d lost a lot of weight. I’d gone from 11 stone to 9 stone. I wasn’t fit, but because there weren’t enough players I had to play … I lost that couple of yards pace. I just lost it. I was very quick. A full-back could have five yards on me and I’d still beat him. But after Munich I couldn’t do that anymore. In a way, I wasn’t surprised to be left out of the World Cup squad … I’m sure the crash took it out of me. I had headaches for a couple of years. I used to have nightmares about the crash and the players who were killed.” (Risoli, 1998, p.32)

Notable mentions should also go to Swansea born players Ray Daniel and Trevor Ford who were considered two of Wales’s finest post-war footballers. However, for very different reasons, the Welsh FA discounted them from representing their country.

Daniel was a respected defender, yet he was banished from playing in the World Cup because he was heard regaling the team with songs from the musical Guys and Dolls. He sang from the track list while travelling on the team coach after they had played one of their qualifiers for the tournament. This incurred the wrath of Herbert Powell, the Welsh FA’s religious secretary, who thought that only hymns should be sang by team members.

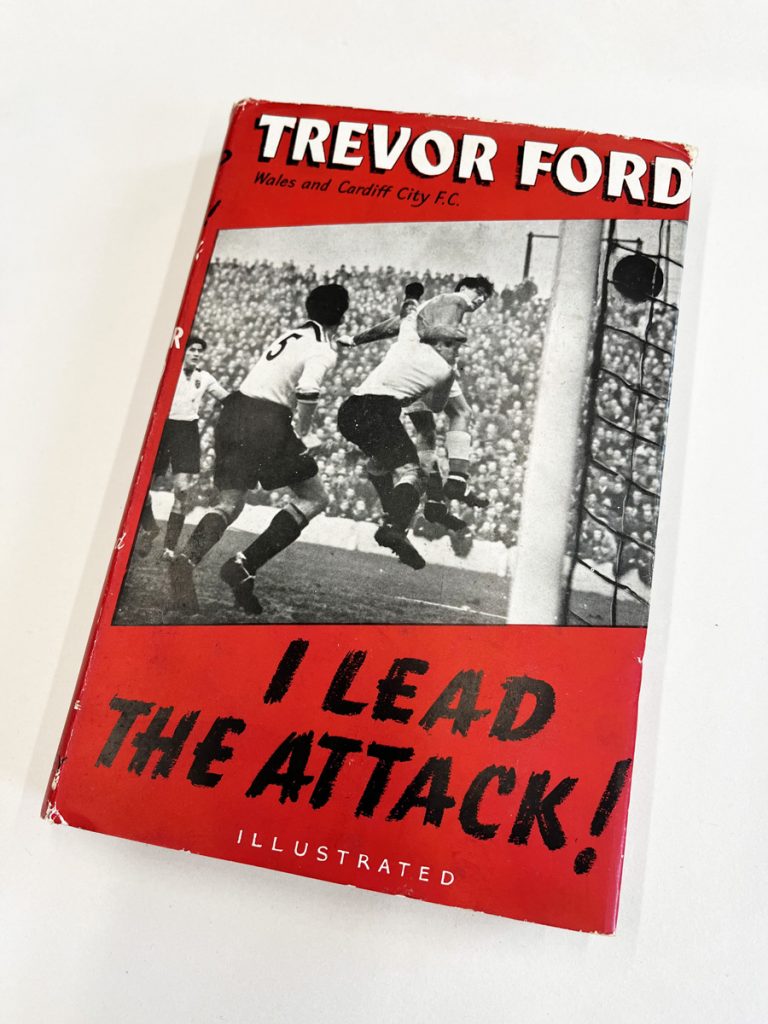

In 1956, Trevor Ford published his autobiography, I Lead The Attack. It was an exposé on the illegal payments by his former club, Sunderland, to their players, including Ford himself. The striker admitted to accepting £100 ‘under the counter’ to join Sunderland from Aston Villa. The FA banned Ford was from league football for three seasons. He went into exile in the Netherlands, where he played for PSV Eindhoven.

Technically, Ford could have still played for Wales, but the selectors would not tolerate someone who admitted to accepting illegal payments. Yet, by ignoring him, the selectors made a mistake. Without him, the Welsh squad was short of centre-forwards, and it would cost Wales dear. Wales surprised the world by advancing from Group 3 after drawing with Hungary 1-1, Mexico 1-1, and Sweden 0-0, and then beating Hungary 2-1 in the deciding play-off. In doing so, they made it to the quarter-final where they faced Brazil and a 17-year-old footballer named Pelé.

They would have to face the Brazilians without their talisman John Charles. He had suffered very strong challenges made by a physical Hungarian side in the first-round play-off, and was now lost to injury. With few choices to replace Charles, it fell to Colin Webster to take the position, who in that crucial game, rarely troubled the Brazilian defence. However, it took almost three-quarters of the match for Brazil to break through the Welsh defence, as Pelé’s flick took him past Mel Charles, and he scored the only goal of the game, ending Wales’ dream of going any further in the competition.

If you would like to read more about the experiences of the Welsh team during the 1958 World Cup, please read Mario Risoli’s When Pelé Broke Our Hearts Wales & the 1958 World Cup (1998. Cardiff: Ashley Drake Publishing), some of which has been referenced here. There are a lot more interesting facts that could not be covered in this blog, and it is a great book.